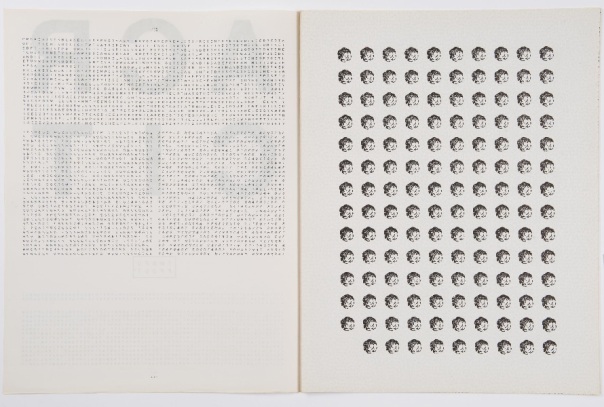

Dick Higgins: Sparks for Piano (1979) The darker, the louder: the lighter. the softer. Duration up to three minutes

What is a legend?

Dwight D.Eisenhower. Suppose Dwight D.Eisenhower. Impossible. Dwight D.Eisenhower an executive. Dwight D.Eisenhower a general not a general. Grant Grant. Grant Grant was a general and is a general and not a man.

Running against Eisenhower running against Santa Claus.

The depression exciting but not interesting. Not interesting. The depression not a legend.

Grant coming and going. Grant on a horse. Grant chewing cigars. Thank you Grant for everything.

1 2 Grant. 1 2 3 4 5 Grant. 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 0 1 2 3.

4 Grant I mean. Thank you Grant.

Sitting Bull famous. Sitting Bull very famous. Sitting Bull on tour. Chief Spotted Dear God Keep You. WIAL. Sitting Bull famous. Sitting Bull with his braves.

Sometimes more. Sometimes Sitting Bull climbing on a hill. Sometimes Sitting Bull calling the ghosts of his ancestors. Sitting Bull in action. Sitting Bull loving Mama Bull. Sitting Bull collecting. Was your Grandfather collected?

Sitting Bull if in action rapidly in action, having to be in action a need for being in thought in action happening in action. But not always in action.

Grant walking. Grant modest but chewing and walking and riding slow. Grant being walking and being drunk and just being and being and being and hurrying.

Sitting Bull being and more. Rapidity. City Bull moving. City Bull changing his mind and making war on the palefaces. City Bull and Al saying “Ugh. Mishugennah.” Sitting Bull possibly heroic, and City Bull certainly is heroic. Sitting Bull become heroic. Sitting Bull becoming. Eisenhower not becoming. Eisenhower hiding. Grant unbecoming but coming and going and being and working.

Is it possible when legends. Is it possible when legends being. Is it possible when history and legends being. History is nice. Can legends and spice be. Spicy bee in chocolate. Can you milk a cow. Can you offer. Offering is always legendary.

Legends and legends.

What legends and what horses and what indians and what soldiers. And what sages and what vegetables. And what meals there are and are being and have been.

Legends are grammar. Legends are the grammar of what we might be being. Hickory is not history. Sophistocation is the enemy of history. When there is no wind there is legend. When there is a big blow there is legend. Legend is hello. There are many legends that nobody has made. Sounds and legends growing like mushrooms in the night. Here we are, amazing. Are we amazing.

Can one be interesting. Can one be interested. Can one be history. Can one be legendary. Being is not historical. Being is history. Having been is history. Being having been. Having been being. That is legend. Legend means sometimes that you wear a hat when you go out of doors. Have you been wearing a hat.

Legend is smiling. Legend and seeing can be brothers.

Legend is donating. Legend is donating the present to the past. Legend is donating being to having been. To having been being. To having been present. To having been the present. Legend is grammatical. Legend is a pussycat and a catnip mouse.

One might have lived in a house. One might have been offering asparagus and tobacco and peas and donating is offering and trees and all the birds what what and what is seen.

Legend is without art. Legend is something else. Legend involves having seen. Legend rides to the moon on a hobby horse. Legend and Isaac. Legend the saints. Legend and dirt. Legend and Dr. Johnson. Legend and what painters are. Legend and what do you enjoy. Legend making action. Action making legend. Action is possible from legend.

Legend is what people do when they are almost asleep. Legend is what people do when they have hidden their minds. Legend is a garbage can, a sacred garbage can. Legend must be without art and with speed. Legend is in poor taste. Legend is without wit. Witlessness. Witlessness and form.

Wits make tables into tables. Then tables cease to be really tables. Tables turning into tables are not legendary. Tables and tables are legendary.

Tables and legends.

This is what tables and legends have done for you.

Abraham Lincoln.

This is called tables and legends.

This is what tables and legends have done for you.

Abraham Lincoln.

This is called tables and legends.

Tables and legends.

If an angel. If an angel dancing. If an angel dancing on a table. If an angel on a table dancing on an alter. Is an angel and altar. Is a table an altar. That is wit. This is not wit.

An angel on a table dancing on an altar.

Angels and tables. The life you save may be your own. Life guard.

If a bird. If a bird dies he lies in the bathtub.

Fat men. Fat men are ticklish.

It is bad luck to walk under a ladder.

Tie a knot and kill your enemy. Tie a knot and cure your ill. Abracadabra. Put in a nickle and out comes Butterfingers and Ray.

Ray.

Sneeze on Monday. Sneeze for danger. Sneeze on Tuesday. Love a stranger. Sneeze on Friday. Sneeze for sorrow. Sneeze on Saturday. See your own true love tomorrow.

What is the use of saving a small fish so that you can eat a large one. What is the use of having been Geographically a child.

These are all familiar having been thoughts. The thoughts of famous people.

But legends must be fast or they are not simple. Simple and true. Legends are wheels spinning and old automobiles coming. Legends are not geographies.

And so having been born was there but is.

I offer you a cigar.

Legend comes from places. Everything comes from the ocean. All the good words begin with C of which there are 7.

Thank you.

May I offer you a cigar.

Drop dead how sad.

What does it mean.

( ) *

Ears.

Thank you.

Legending is done by ears. These ears are located in the center of the forehead, assuming that the C’s are in line. Lines do not curve. They sometimes swurve but they never curve. To see with your ears, what happens is not a line. Not if a legend. What happens is on the wall.

One might let the happenings happen.

One might not.

One might contribute.

1 and 1, and 1 in a box.

Being better.

1 might offer a fly his freedom. 1 might be clearly red. 1 might reflect the sun. 1 might not have enough air. 1 is many things.

Who are people anyway.

This is the most useless thought ever.

1 in a spaceship. What is 1 I will make 1. A little 1.

Here I am.

Once I climbed a hill, not a legend.

Here is a hill, not a legend.

A hill. Beginning. I climbing. Nous voyons …. no legend.

A hill. Climbing. I, fat, with grease in my hair.

A monkey’s cheek pouch. To damage. Abracadabra. Abstractly accessible. Banausic beans. Chug chug.

To the tune of twinkle twinkle little star.

Thanking and offering makes everything clear.

Somebody has ruined the soup.

The End

Here we come to the end.

Legends comes form the sixth sea, after everybody else has gone away.

Legends do not know.

Legends are what never know anything.

Legends move.

Ivor a legend. Everything is clear.

I thank you.

The End

Still not the end. I cannot call on the end.

Everything is clear.

I thank you.

Autumn, 1959

* Nobody home.

SOURCE: First published in 1960 by Bern Porter as a pamphlet. This text from Dick Higgins, Legends & Fishnets (Barton, Vermont & New York, New York: Unpublished Editions: 1976), 11 -17. For the original formatting see the PDF here. Spelling as in original.

APPENDIX

In his essay “The Strategy of Each of My Books,” Higgins writes:

What Are Legends (1960), my first book, is the theoretical text which goes with Legends and Fishnets (1958-60, 1969; published in 1976). It exemplifies my near-obsession with unifying my theory and practice, written as it is in my “legend” style; this style uses few verbs in the indicative mode, substituting participles wherever possible, in order to get a pictorial effect in words. Important conceptual models to me were certain late Latin poems in which strings of participles provide the movement of the poem (e.g., the “Stabat Mater”) and the last part of the De Quincey “English Mail Coach,” as well as the obvious modernist texts by Gertrude Stein and others. I printed it myself when I was at the Manhattan School of Printing, using a handlettered text and found-illustrations by Bern Porter, a highly original graphic artist and writer from Maine whose work I have admired for many years.

SOURCE: Dick Higgins, Horizons: The Poetics and Theory of the Intermedia (Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press, 1984), 118.

Higgins was also a publisher of Unpublished Editions, so perhaps the cover blurb for Legends & Fishets can be seen as a further author’s note:

“Must a story consist only of what is told? Or can it also lie in the language? Or in the interplay among the ideas and images embodied in the words?

In Legends & Fishnets Dick Higgins sets out to use a whole bevy of unorthodox means of narrative. The legending idea is simply that the image of a person or thing can be reverberated in the mind to add to its stature – the man or woman may be small, but the shadow can be huge. These stories are told in terms of the shadows and afterimages of the subject. Higgins’s interest in this process is not a recent one – some of the stories were begun as early as 1957, and they were written on and off until 1970. The use of assemblages of participles (and its implicit avoidance of the verb to be) produces a strongly visual effect, heightened by very concrete language. The principle at work is William Carlos Williams’s formula “No ideas but in things!” more than some development out of Gertrude Stein’s concept of the continuous present, which these pieces superficially resemble in some ways, and to which Higgins feels sympathetic but unrelated. This the reader will discover when he comes up against Higgins’s emphasis on moral principle (in the lineage of Emerson) and interest in all stages of the time process, not just the present as with Stein.

These stories cover a full range of expression – from the farcical (“Sandals and Stars”) to the comic (“The Temptation of Saint Anthony”) to the nostalgic (“Ivor a Legend”) to the lyrical (“Women, like horses”) and more. If the expression is heightened by the form, then the form is justified. And it is here, on this assumption, that Higgins has hung his hat.”

*

Higgins’ work is still principally (un)available as second hand copies of books published through his own Something Else Press, Unpublished Editions, and Printed Editions, although Station Hill Press published a selected poems.

Higgins’ trilogy of critical essays remains a vital sourcebook of an artist thinking critically about practices of work with which they are themselves implicated as a practitioner. Ubu Editions have posted the second volume Horizons: The Poetics & Theory of the Intermedia (1984) online, and the third Modernism Since Postmodernism: Essays on Intermedia is still in print (scroll to bottom of page).

A READER that drew from the entirety of Higgins work would be a wonderful thing. Online sources for Higgins’ work include (at Ubuweb) his 1965 Great Bear Pamphlet A Book About Love, War & Death Canto One. The excellent Light & Dust have a complete collection of Higgins’ metadramas.

Trying to identify points of connection with contemporary practice, I illustrate this edition of the DEMOTIC ARCHIVES with, firstly, Higgins’ Intermedia Chart (1995), interested in how its proposition fits within the contemporary interconnections/ movement of language between formats/ contexts within art writing. It should be viewed within a history of diagrams in his practice, including “Some Poetry Intermedia” and “Five Traditions of Art History” (both 1976).

I also include examples of his musical scores, acknowledging Higgins’ own contention that “composer” remained a key identity for thinking through the entirety of his work across writing, performance, painting, book making and music (criticism?) (amongst others). As he told Nicholas Zurbrugg in an interview in 1993:

“I would say that I am indeed a composer, which is actually where I began, but that I compose with visual and with textual means. That’s a fairly accurate way of describing my approach. A composer is apt to work with more design in his approach than a prose writer, or a poet, or a visual artist, is apt to do. That is, the composer maps out the architectonics of a musical work. And that basic approach is the one I’ve carried on over all the areas that I’ve investigated.

I’m a person who sets out his form, usually in advance, and then follows it. It’s not that I don’t appreciate the spontaneous departure from that. But I’m usually happiest, and keep my best sense of proportion, when I allow the spontaneous to work on the details of things, but where the overall structure is one that has been preconceived and that I continue to use as a matrix. So I would say I was a composer, but not necessarily of music. Something like that is a good way to describe me. And if people think of me as that, I’ll be quite happy. ” (211)

SOURCE: Nicholas Zurbrugg ed. ART, PERFORMANCE, MEDIA (University of Minnesota Press, 2004).