This edition of the DEMOTIC ARCHIVES OF ART WRITING points elsewhere, holding itself like one of the studied poses in Guy de Cointet’s theatre pieces. Firstly, to the fantastic archives of Guy de Cointet’s work here. Secondly, to the slim, elegant monograph edited by Marie de Brugerolle.

Considering these resources, I wondered what aspects of de Cointet’s work could be most usefully presented on VerySmallKitchen. Perhaps the stills of performance works such as Tell Me (1979) and A New Life (1981) are most relevant…

In this mute form (only brief vimeo clips exists online), I find de Cointet’s stylised acts of reading and speaking alongside boldly coloured geometric shapes and furniture, articulate a scenography of art writing.

By this I mean a certain staging emergent from the workings of language within art practice, which can be traced from de Cointet’s work through to current lecture performances of, for example, Ruth Beale, Falke Pisano, and Francesco Pedraglio…

I was also intrigued by de Cointet’s use of code, particularly TSNX C24VA7ME: A Play by Dr.Hun (1974, but recently published by New York’s 38th Street Publishers). If de Cointet’s theatre pieces suggest a scenography of art writing, then these works suggest writing (as a physical act but also as a form of publication, distribution and community) as code, both with and without key(s) for decoding.

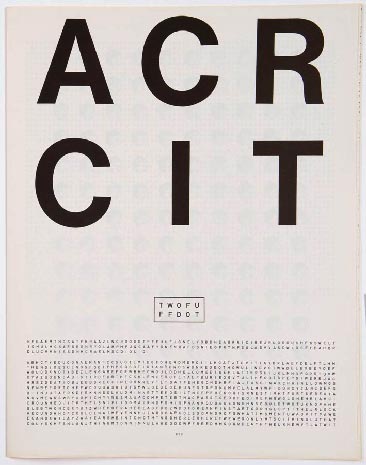

Perhaps, for our purposes here, these come together in ACRCIT (1971), originally published by the artist in an edition of 700 copies. Stills of de Cointet’s Tell Me performance show ACRCIT being read and wielded as text and prop…

In her recent monograph Marie de Brugerolle describes ACRCIT as:

…a newspaper published in Los Angeles in 1971. Seven large pages, folded in two, made a newspaper of 14 recto-verso pages. It was silkscreen printed by Pierre Picot, a French artist who worked at the California Institute of the Arts. The title is printed in bold lettering; the page numbers are coded in letters. The paper includes texts encrypted in various manners: Morse Code, pyramids of figures, magic squares, and Mohammed’s signature of a double crescent (mirror writing mentions that the prophet traced his mark without lifting the point of his sword from the ground) all occupy the space like decorative motif’s, as do small palm trees.

This publication contains the principles at work in de Cointet’s other books and drawings: letters and figures function more as signs than as signifiers. De Cointet explores language by deconstructing it, in order to show that it is a question of systems. Reducing these systems to visual puzzles, he puts the reader in position of beholder, returning to a prelogical state when words were shapes and sounds. His anatomy of language is similar to experimental poetry of the early 20th century, influenced by Stéphane Mallarmé’s Un coup de dés jamais n’abolira le hasard (A Throw of the Dice Will Never Abolish Chance).

The early 1970s was also the heyday of structuralism and de Cointet was an informed reader of Barthes, whose essays deciphered systems and structures in order to reveal new relationships between form and meaning. With de Cointet the beauty and mathematical harmony of the world is translated into words and figures. This poetic alchemy relies on game-like systems, using chance as a creative principle. Language becomes a simultaneously mental, visual, auditory, and sensual experience.

De Cointet placed ACRCIT in free newspaper distributors on the street in Los Angeles. Passersby could thus procure an original if incomprehensible artwork, few of which were probably preserved. Jeffrey Perkins, the friend who was housing de Cointet at that time, recalls that the artist enjoyed the anonymity and “obvious invisibility” of things, which perhaps explains why the title itself, ACRCIT, remains mysterious. Several interpretations are possible. Homophony suggests the French word écrit (“written” or “writing”), or even ASII (American Standard Code for Information Interchange, one of the computer protocols that converts letters of the alphabet, punctuation marks, and other symbols into numbers).

Indeed, de Cointet used the binary system of 0 and 1 in his newspaper, although to indicate insignificant things. “Only the small secrets need to be protected,” Marshall McLuhan reportedly said. “The big ones are kept secret by public incredulity.” We know that McLuhan bought one of de Cointet’s books in 1979, though there is no evidence that they ever met. But de Cointet certainly read McLuhan, and in ACRCIT he quoted the last paragraph of McLuhan’s Introduction to Understanding Media:

When radar was new it was found necessary to eliminate the balloon system for city protection that had preceded radar. The balloons got in the way of the electric feedback of the new radar information. Such may well prove to be the case with our existing school curriculum, to say nothing of the generality of the arts. We can afford to use only those portions of them that enhance the perception of our technologies, and their psychic and social consequences. Art as a radar environment takes on the function of indispensable perceptual training rather than the role of a privileged diet for the elite. While the arts as radar feedback provide a dynamic and changing corporate image, their purpose may not be to enable us to change but rather to maintain an even course toward permanent goals, even amidst the most disrupting innovation. We have already discovered the futility of changing our goals as often as we change our technologies.

At the dawn of the launch of the internet as a communications system devised by the US Army, de Cointet used coding methods that, although “low tech,” were equally sophisticated and widespread. What could be quicker and more direct than a free newspaper, openly available on the street, for passing information from hand to hand? Later, ACRCIT would be used in the theater pieces Iglu (1977) and Tell Me (1979).”

SOURCE: Marie de Brugerolle, Guy de Cointet (JRP Ringier, Zurich, 2011), 25-27.

Having copied this out I look back up at ACRCIT, considering again how de Cointet’s work offers sources both for scenographies of art writing, text as prop (held, pointed at, furniture) and codes as models for publication, distribution and practice more broadly.

I wonder how ACRCIT can be read in relation to its concrete poetry contemporary (also formed in relation with systems theory and communications technology), and how that too enters the present… different and combining… As game as enigma I note again Maria Fusco’s conception of art writing as riddle, the art object greeted by the writer as like for like, “essential obscurity with essential obscurity.”

As de Cointet begins and ends his contribution to the 1980 “Foreign Agents” issue of FILE magazine: “I can no longer find my way. / I wander about utterly confused./ Finally I stand still and engage in a short monologue…”

SOURCE: Maria Fusco, “Say Who I Am/ Or a Broad Private Wink,” in Jeff Khonsary and Melanie O’Brien, Judgement and Contemporary Art Criticism (Fillip Editions, 2010), pp73-80, p73. Image: still from Tell Me, Rosamud Felsen Gallery, Los Angeles, 1979.