_

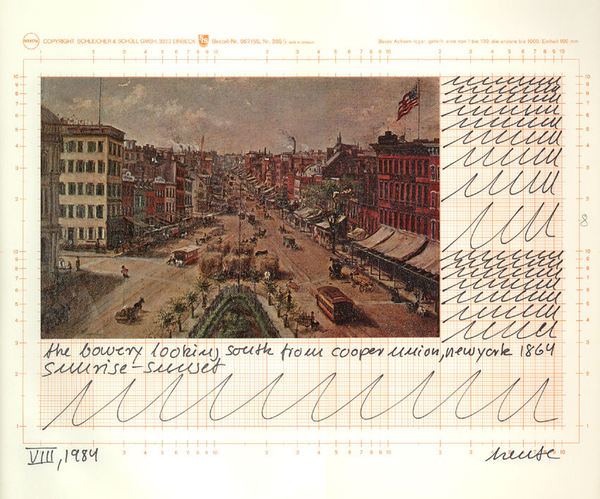

“I’ve thought of you so often these past few days, and also occasionally about the time long ago when, as you will remember, you visited me in The Hague and we walked along Trekweg to Rijswijk and drank milk at the mill there. It may be that this influenced me somewhat when I did these drawings, in which I have tried as naively as possible to draw things exactly as I saw them.”

From: Vincent van Gogh

To: Theo van Gogh

Place/Date: The Hague, Saturday, 3 June 1882

25.2.12 (Amsterdam)

I’m sitting on a bench in the Museumplein in Amsterdam.

I’m facing the Van Gogh Museum.

A big banner on one of the facades of the museum says:

‘The Bedroom has returned’.

Under the big bold black letters is a reproduction of the bedroom painting by Vincent Van Gogh.

It is only lately that I feel attracted to Van Gogh and his work.

It is the figure of Van Gogh as the romantic artist that fascinates me the most.

The portrayal of his struggle encapsulated in a world that could not or did not want to understand him is what strikes me.

In the letters to his brother Theo I could detect a certain sensitivity of the everyday and banal elements of reality.

Van Gogh trusted his vision, he immersed himself in it and held onto it as his only ally. By being immersed in this reality he could perhaps transcend his own existence and become one with this reality.

The erasure of all external factors is a charming idea. It gives the feeling that only him alone equipped with his vision of the world was the world.

The bedroom in this context was a place of refuge for Van Gogh in which he could put this vision of the world to rest.

Where did The Bedroom (painting) return from?

Where did it travel to?

The ‘re-turning’ of The Bedroom (painting) also designates a primary return of the painting to its metaphorical bedroom – The Van Gogh Museum.

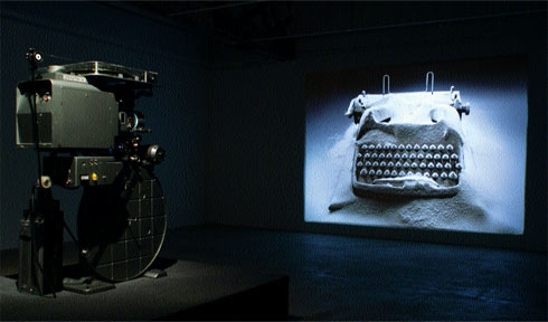

Work In Progress: Self Portrait as Van Gogh Sitting On His Chair In His Famous Painting - The Bedroom, Ohad Ben Shimon & Veniamin Kazachenko, 2012

The painting now, embodied with Van Gogh’s aura can go back to sleep.

It is a curious incident in which a content of a painting dictates its contextual reception.

The Bedroom (painting) rests in its bedroom (museum) and the visitors of the museum acquire the position of witnessing an artifact with a human quality – fatigue.

The painting continues to hibernate in an eternal winter sleep and the museum maintains its status as the all containing reservoir of art.

I see two birds passing.

Then a sound of two planes roaming the skies.

It is the end of the winter.

Nature will soon awake to a glorious yellow-blue spring.

*

16.2.12 (Paris)

Photo: Daillier Fabien

_

“Shit!”

“What?”

“I forgot my camera. Do you have the key? Open the door! I need to get my camera”.

“I don’t have the key.”

“Does Lev have the key?”

“No. Nobody has the key.”

“Shit!”

“Come on! We gotta hurry, the train leaves in half an hour”.

It’s 5 thirty in the morning.

We’re in Amsterdam. We are on our way to Paris.

–

“Bonjour. Can I see your tickets?”

We show our tickets.

“This is not your cabinet”.

Lev has already drunk a beer and is searching for his second one.

“If you guys want to sit near a big table you can sit in the cafeteria cabinet”.

We go sit in the cafeteria cabinet.

Ben goes to look for beer. It’s 6 fifteen in the morning.

“There is no beer here” he says as he comes back from the cafe lady behind the counter. Ben takes out a deck of Russian cards and we play some Russian card game in which there are no winners, only losers.

The train stops at Rotterdam.

We consider stepping out for a smoke but by the time we have made our minds to get up of our seats, the conductor lady says that the train is leaving.

We leave.

We stop in Antwerp.

“Should we try and have a smoke now?”

“Yeah”

We go to get coffee.

In line before us is one of those ladies with small change. She keeps counting her change. It takes her about 10 minutes.

By the time we get our coffees and try to go step outside the conductor informs us that it is too late to get out.

The train leaves. The next stop is Brussels. We will try to have our cigarette smoke there.

We stop in Brussels.

We smoke.

We get on the train.

We move.

We continue moving for a bit, then we fall asleep and wake up in Paris.

Ben and Lev leave the train while I stop by the toilet to take a piss.

I piss and get off the train.

As I walk on the platform towards the escalators I see Ben and Lev from a distance with 2 police guys that are asking them all sorts of questions and showing them some badges.

As I approach them I hear the police guy saying to Lev that he needs to check his bags.

I conclude quickly that its some kind of drug inspection.

I remember hearing something early in the morning that Lev has some white powder present that he got from someone for someone else. Not knowing exactly what Lev is carrying with him I decide to continue walking without making any eye contact with them.

I try to observe what’s going on from the other side of the platform but the parking trains block the sight.

I try to come up with a plan of what to do as I imagine Lev and Ben being arrested for smuggling drugs into Paris from Amsterdam.

I walk out of the station trying not to be noticed and go search for an ATM machine to take out money so that I can pay for a hostel for the night.

As I don’t have a mobile phone nobody can reach me and I can’t be tracked by the police.

I get out some money from a machine and ask a guy for the directions to Centre Pompidou which is near where our exhibition will take place. The guy points me in the direction and says it’s quite far.

I decide to go back to the station one more time before I depart towards Centre Pompidou. I reach the crossroad and try to be out of sight of the police. I see Ben waiting outside the station by himself without any bags. I signal to him to come meet me down the road as I’m afraid the police will connect me with Ben and Lev.

Ben meets me at the end of the road and says “It’s over”.

I ask him if Lev is arrested. He says yes and that they took all their bags.

After we walk for a bit more I suddenly see Lev sitting in a cafeteria with the bags.

It appeared to be that Ben was just fooling around and that eventually nobody got arrested.

He said that indeed the police, whom were customs officials, opened Lev’s bag and found a small bag with white powder in it and asked him what it was. Lev said to them that it’s a small present from a friend and that he is an Artist coming to Paris for an exhibition and that the white powder is just plaster powder for a sculpture he is going to make.

17.2.12

I’m in some kind of youth hostel near Montmartre. I’m already 33 years old and I’m still sitting around 18 year olds fighting for a second round of breakfast consisting of bad coffee, small croissants and artificial orange juice.

Ben is upstairs showering and Lev is downstairs having breakfast. I’m sitting in the entrance of the hostel watching different young people pass by.

2 guys next to me are speaking Spanish. Some Japanese girl is touching her iPhone and some other Spanish guy is writing “Fuck” on a chalkboard wall that is here for the visitors of the hostel to write stuff on. Then he writes “Room 203, I’m waiting”.

I store my big black bag in the luggage storage room. I hope we will be able to come back today to pick it up. I roll myself a cigarette and go outside for a smoke.

18.2.12

I’m outside of an art shop sitting on some metal fence thing smoking and writing.

Ben is inside shopping for paper and oil.

Afterwards we will have something quick to eat and go back to the exhibition space to meet up with the others.

Tuesday night is the opening of our show in Espace des Blancs-Manteaux around the corner of the Centre Pompidou.

My feet are hurting from too much walking.

A guy is standing about 10 meters from me with a grey jacket and watching the traffic go by.

I go check in on Ben inside.

There are many people inside the large art shop.

Ben is checking the acrylic department.

He says “I’m so stupid, why didn’t I take some French speaking person with me?”

I go outside of the art shop and sit on the sidewalk.

A car parks.

A French couple talk some French and walk.

An old lady is walking her cat with a yellow leash.

I’m hungry.

I’m tired.

I’m in Paris.

–

Dinner was had. Chinese.

Ben is drilling.

Lev is searching for something on the internet.

We are inside the huge exhibition space.

It’s 22:00 o’clock.

Rain is raining outside.

Part of the exhibitors have already put up their stuff on the white panels.

There is nobody besides us here now.

I was told the space used to be a mental institute before and after that a meat market.

“Hey, how did Ceel use to say ‘Record’ in French?” Lev asks and then answers to himself “Ah yes, Register, Register.”

“…but he’s exhibiting in the Biennial,” Ben says.

“Which Biennial?” I ask.

“I don’t know. What’s a biennial?” Ben asks.

Now we move the table closer to the electricity so we can have some music on the laptop.

Lev needs my pen to write down ‘Magneto-scope’. I use my other pen.

It’s Saturday night.

“I’m not going to buy a fucking Magneto-scope (the french term for a VHS Player) for 40 euros”, says Lev.

Ben continues drilling.

19.2.12

It’s a beautiful sunny Sunday morning.

Paris is waking up.

I bought a juice from the supermarket that says it has 12 fruits and 10 vitamins in it.

I’m opening it.

It makes the sound of a juice bottle being opened.

I drink the 12 fruits and 10 vitamins.

I search for my tobacco in my pocket and realize that I must have forgotten it somewhere.

I drink some more of the vitamins.

The Parisians seem to be minding their own business. They walk by me with baguettes and dogs.

A guy on a skateboard rolls down the sunny street.

The shop’s name sign in front of me says “Look”.

The birds are birding.

I like mornings in Paris.

A lady walks by with flowers.

Then some more people walk by.

A young puddle dog sniffs some poop on the sidewalk and then pisses on it.

A guy runs.

A car cars.

I go back to the hostel to see if the others are already awake and showered.

–

I’m back in the hostel.

I’m waiting for Ben and Lev to come down.

Above the reception desk are 3 clocks.

The left clock says 2 o’clock and “Los Angeles” under it.

The middle clock says 11:00 o’clock and “Paris” under it.

And the right clock says 7 o’clock and “Tokyo” under it.

A CCTV camera connected to a small monitor on a fridge displays various video shots of us in the interiors of the hostel.

20.2.12

I’m tired.

The radio is playing classical music.

I’m going to sleep.

21.2.12

I’m standing on a sunny corner of Paris.

Tonight is the opening of our exhibition “Donner du temps au temps” which translates into “Giving time to time”.

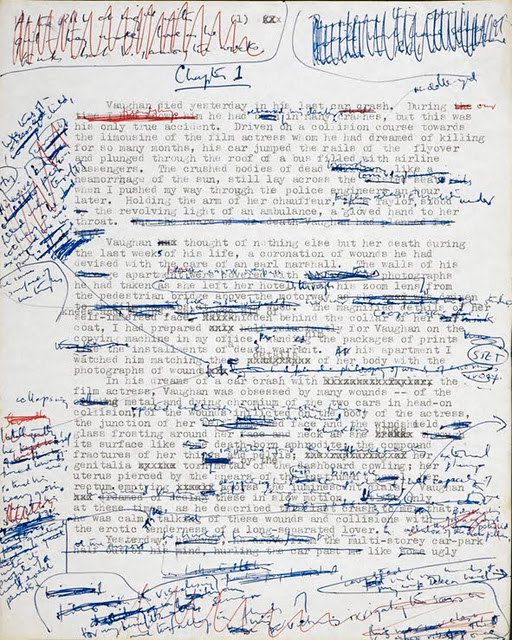

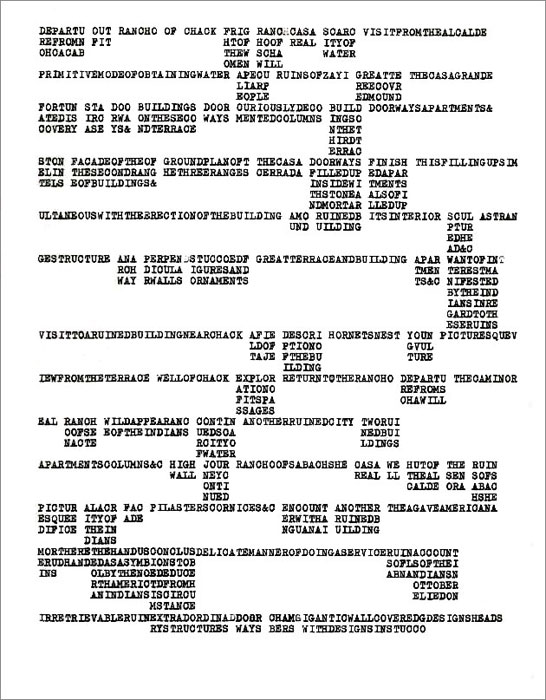

Me and Ben will do a dialogue-painting-performance during the 3 days of the exhibition in which he will work on his painting whilst I talk on a microphone and have a reflective dialogue with him in front of the public.

He started already by painting a big black hole on the 6 x 2.5 m paper.

Lev is working on his installation upstairs.

Yesterday we were interviewed about our work and how it is related to the theme of time and why we chose to work in-situ.

I’m starting to get hungry.

For the last 3 days we had falafel and shawarma.

22.2.12

I’m standing on a sunny corner of Paris outside our exhibition space in the Jewish quarter.

Last night was our opening. Many people came.

Ben was painting whilst I was talking to him with a microphone so that the audience could hear our dialogue.

At first the painting started with a black hole and throughout the time/evening and our talk it included also a black swan.

The idea was that it would combine somehow two distinct points of view simultaneously. The macro level or cosmic elements of the universe and the down to earth, everyday, micro level of the human animal. Ben was the cosmic one, I was the everyday.

Towards the end of the event a guy approached our installation and asked if it is possible to have it in smaller scale. While I was performing with Ben I asked the guy out loud with the microphone how big he wanted it. He made a gesture with his hands of something like 100 x 80 cm. I asked Ben with the microphone if he could do it in that size. He said yes whilst he continued working on the painting.

At some point Ben finished and talked to the guy who identified himself as Monsieur Daniel. When I asked him what does he do for a living he said it’s not important.

He continued to give Ben complements of how much of a genius he is and he expressed many prospects about Ben becoming famous and warned him of being around the wrong people.

The girls that were responsible for the selling of the works in the exhibition took Monsieur Daniel aside and wrote down his phone number.

–

Photo: Dallier Fabien

_

We’re at Notre Dam.

The tourists flood the square in front of the Notre Dam. A young American girl is wearing a hat next to me with the price sticker still on it saying 17.90 euros. I wonder if she knows it’s still there. She seems to be having a casual talk with a guy who appears to be Thai. She asks him if he went to the top yet. He says no. She asks if it’s because he’s afraid of heights. He says no and gives some explanation.

The American girl has an American accent. The Thai looking guy has an Arab accent for some strange reason.

Various other tourists pose in front of the Notre Dam and take pictures of themselves as tourists standing in front of the Notre Dam.

–

I’m back in the installation-performance-painting-dialogue.

I’m seated on a chair.

The microphone is next to me.

I’ve eaten a cold lasagne for 5 euros.

The painting has taken a new form. After I came back from the walk Ben was busy making fine details of the painting.

Ben and me started talking while the audience were watching us paint and talk. At some point we reached the conclusion that the painting has reached a certain stage and that now it was becoming static from the significance it had received as a work of art with a certain value. We tried to think what should be the next step. One of the visitors asked if the painting has a title. We replied that it doesn’t have a title.

At some point Ben opened a tube of silicon and started smearing it on the painting together with some black paint. Then he made some more scribbles with some yellow and red crayons. It was becoming less of a painting and more of a child’ drawing. Then Ben took some more oil and acrylic paint and started erasing the black hole. It became one big black mess of nothing.

Ben continued obliterating the painting until it became a big messy cloud of paint. The black swan managed to survive and remained in its place without damage.

I said to Ben and to the audience that I feel much more relieved now. A certain weight was removed from the painting.

I remarked that it’s a bit like in Buddhism. It is a process that changes all the time. Yesterday night it was still a painting with a black hole and black swan. Now it has changed. It has transformed into something else. It doesn’t matter that it can’t be named now. Only that it existed for a certain moment and in a way died at a certain moment.

It became lighter this way.

I asked Ben if he felt relieved also. He said sure. He smeared some more paint around and then we went to get some USB sticks and wine.

A few visitors pass by the different art works in the exhibition that are installed in an art fair fashion.

They walk.

They stop.

They look.

Then they move onto the next booth.

They scratch their heads.

They look at the sign that is suppose to explain what this is about.

Then they look back at the work and move on.

23.2.12

It’s 6:25 in the morning.

We’re in Gare du Nord metro station

The train is leaving.

We are on it.

We drink coffee.

The rain rains outside.

–

We stop in Brussels.

We smoke a cigarette.

When we come back from the smoke we see that some old guys have taken our seats which we took from them.

Ben and Lev go over the documentation images of the exhibition.

The girl sitting next to me is sleeping.

She has a purple shirt, dark black pants, dark shoes and dark earrings.

She has one leg crossed over the other.

She moves her legs a bit in her sleep. Her black scarf is hanging on the hanger next to her. He face is facing the window. She has a dark coat worn backwards on her keeping her warm.

–

It’s 8:30 in the morning

I try to have a little nap but can’t manage to fall asleep. The old guys that took our seats that we took from them are talking a mixture of French, Flemish and Dutch.

Mist is covering the fields outside.

The train stops in Antwerp.

The sleeping girl next to me moves a bit. Then she wakes up and checks her iPhone. It says 8:36. Then she goes back to sleep.

The ticket lady walks up and down the cabinet.

Some Belgian people outside are riding their bikes.

The voice of a male conductor comes out of the speakers and apologizes for a delay of 10 minutes in 3 different languages.

The trains stops at Rotterdam.

Ben says “Come on, let’s get off. This is our stop”.

I stop and get off the train

Notes

The following exchange took place by email from 28th February – 1st March 2012.

VERYSMALLKITCHEN: Do you ongoingly keep diaries like this or does it require the focus of a particular event or commission?

OHAD: My diary writings have been an ongoing project/format of mine since a residency I was invited to visit in Hoyerswerda, Germany in 2008. Back then it was meant to document the last days of a group of artist that were inhabiting an old abandoned apartment block that was destined to be demolished when the residency terminated.

Since 2008 I have occasionally written these diaries (to be performed in a kind of Lecture-Performance format) on travel (extra-territorial motion tends to surface these concerns) whilst participating in Exhibitions, Festivals and Conferences across Europe. They are usually part of and apart from the actual experience taking place. I see my position in these encounters as a cross between a pseudo-journalist/art critic and a group psychologist.

This is the first time that a diary like this is not filtered primarily through my voice in a live performance in front of a live audience.

VERYSMALLKITCHEN: What is the absence this writing gives shape to? Looking at the texts you sent me, writing constructs this absence whilst also providing commentary, evidence, naturalistic detail, anecdote…

OHAD: Perhaps the absence you correctly describe is an absence of this diaristic voice…

VERYSMALLKITCHEN: I’m thinking how Maurice Blanchot begins his discussion on Recourse to the “Journal” in “The Essential Solitude”:

It is perhaps striking that from the moment the work becomes the search for art, from the moment it becomes literature, the writer increasingly feels the need to maintain a relation to himself. His feeling is one of extreme repugnance at losing his grasp upon himself in the interests of that neutral force, formless and bereft of any destiny, which is behind everything that gets written. This repugnance, or apprehension, is revealed by the concern, characteristics of so many authors, to compose what they call their “journal.” Such a preoccupation is far removed from the complacent attitudes usually described as Romantic. The journal is not essentially confessional; it is not one’s own story. It is a memorial. What must the writer remember? Himself: who he is when he isn’t writing, when he lives daily life, when he is alive and true, not dying and bereft of truth. But the tool he uses in order to recollect himself is, strangely, the very element of forgetfulness: writing. That is why, however, the truth of the journal lies not in the interesting, literary remarks to be found there, but in the insignificant details which attach it to daily reality. The journal represents the series of reference points which a writer establishes in order to keep track of himself when he begins to suspect the dangerous metamorphosis to which he is exposed. (The Space of Literature, 29)

…

OHAD: In the performance together with Veniamin Kazechenko, we mainly had an internal dialogue between ourselves and to a small extent between us and the audience. Yet it felt predominantly different than the kind of monologue I’m used to.

Still, as you suggest, the performance does fill in an absence of a sort. Yet I’m not sure it is in direct relation to the text. Or maybe, the diary could be thought of as an account between a 1st and 3rd person, in comparison to the performance which was more of an account between a 1st and 2nd person.

VERYSMALLKITCHEN: You also offer a narrative of an artist’s life. I recently read YEAR from Komplot in Brussels, which in its contents and design consciously constructs a narrative of a contemporary artist’s lifestyle and personality as part of its presentation of the work…

OHAD: The narrative of an artist’s life is something that indeed interests me in the last few years. I’m aware of the Bildungsroman and the Künstlerroman genres which are two forms that interest me, yet I’m still puzzled as regards to what kind of coming of age my texts could be referring to or point at.

There is a point in the diary text from Paris where I’m writing about me being 33 years old sitting in a youth hostel of 18 year olds’ fighting for a second round of free coffee. I mean, this kind of coming of age never seems to come. Maybe it is an account of these days in which adulthood is postponed to an indefinite future.

VERYSMALLKITCHEN: In the first part of this post you work with/ from the narratives-become-myths of Van Gogh –

OHAD: To be honest I’m still trying to discover what part of this myth enchants me the most. It probably has something to do with the discrepancy between the artist’s own subjective perception of reality and the public personification and portrayal of the artist by society/culture.

I’m also interested in a kind of testimonial level or witness experience coming from the artist usually in contradiction to the accounts of the artist by society. What I mean to say is that I trust artists more in their historical accounts. Something in the figure of the artist lends itself to a kind of historical validity or accountability which perhaps the myth of the artist tries to de or re-construct.

VERYSMALLKITCHEN: My initial thought for how to publish this post was the Van Gogh piece, then the diary beginning 21.2.12 and ending with 23.2.12 “It’s 6:25 in the morning”…. maybe starting with 19.2.12 but also maybe good in the blog post itself to keep a focus around the performance? The whole diary could be available as a PDF.

OHAD: I’m quite puzzled as how to deal with it. For me usually the diary texts are in a way a kind of round artistic gesture in the sense that I start writing at a specific time (and place) and I end in a specific time (and place – on location in front of an audience).

In that sense it is a performative kind of writing. It’s hard for me to carve out pieces from it. Yet I’m aware it’s quite long for a blog post. So I leave it up to you to decide how to handle it. Maybe have 2 posts (part a / part b?). And I have this nice piece of text from Gertrude Stein which i read on the train today:

Once upon a time I met myself and ran.

Once upon a time nobody saw how I ran.

Once upon a time something can

Once upon a time nobody sees

But I I do as I please

Run around the world just as I please.

I Willie.

(Gertrude Stein, Willie and his singing, From The world is round.)

OHAD: I love the first sentence! Once upon a time I met myself and ran – beautiful!

*

More about Ohad’s work is here. See also post one, post two, post three and post four.